Biodiversity Technology: innovative solutions for biodiversity conservation and monitoring

Protecting biodiversity is no longer just a matter of goodwill: it is a technological challenge. As biodiversity loss accelerates, new approaches are emerging at the crossroads of ecology, data science and engineering. This is the core purpose of biodiversity technology: using digital tools and advanced sensors to better observe, understand and safeguard ecosystems.

In this article, you will discover how these technologies – connected sensors, AI, remote sensing, drones and citizen science apps – are transforming the work of scientists, NGOs, public authorities and businesses. You will also see how specialist providers such as Natural Solutions are already supporting concrete conservation projects around the world.

You will come away with a clear overview of existing solutions, real-world use cases, key limitations to anticipate, and practical ideas for integrating these tools into your own projects.

Understanding biodiversity technology and why it matters

Biodiversity technology refers to all digital and hardware technologies used to observe, measure, analyse and manage biodiversity. It combines three main pillars:

Ecology: knowledge of species, habitats and interactions between organisms.

Data science: data collection, processing, statistical analysis and modelling.

Engineering: development of sensors, software platforms, transmission networks and algorithms.

The goal is to address major challenges: habitat loss, climate change, pollution, species decline, as well as human pressures (urbanisation, infrastructure, overexploitation of resources). Biodiversity technology solutions make it possible:

to track changes in species populations in near real time;

to quickly identify warning signs (invasive species, abnormal mortality, deforestation);

to assess the impact of public policies or development projects on ecosystems;

to prioritise conservation actions where they will be most effective.

Several major categories of technology can be distinguished:

Sensors (camera traps, acoustic recorders, GPS tags, environmental sensors).

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to automate species identification and detect complex patterns.

Remote sensing (satellite imagery, LiDAR, aircraft) to analyse landscapes at large scale.

Drones to collect very high-resolution data in hard-to-reach areas.

Citizen science applications enabling the public to contribute to data collection.

The benefits are significant for:

Conservation practitioners and researchers: more accurate data, long time series, advanced analyses.

Governments and local authorities: robust evidence for protection policies, spatial planning and regulatory reporting.

NGOs: better project monitoring, impact demonstration, improved ability to engage funders.

Businesses: measurement of nature-related impacts and dependencies, biodiversity strategies, non-financial reporting.

Specialised providers such as Natural Solutions offer integrated solutions – software platforms, sensors and dedicated support – to ensure these technologies are truly operational in the field and serve conservation outcomes.

How technology is used to monitor biodiversity in the field

Biodiversity monitoring today relies on a set of complementary tools able to collect continuous data, often in remote or difficult environments. Among the main in situ monitoring systems are:

Camera traps: motion- or heat-triggered cameras that discreetly capture images of wildlife.

Acoustic recorders: audio sensors that capture bird songs, mammal vocalisations, underwater sounds, and more.

GPS tags: devices attached to animals to track their movements, migrations and territories.

Environmental DNA (eDNA): sampling of water, soil or air to detect genetic traces of species present.

IoT sensor networks: connected monitoring stations (temperature, humidity, water quality, noise, light) linked to data platforms.

Data from these tools are:

Collected in the field by teams or autonomously (sensors deployed for several months).

Transmitted via cellular, satellite or radio networks, or retrieved during site visits.

Centralised in databases and specialised platforms, often accessible through dashboards and interactive maps.

Analysed to produce indicators: abundance, diversity, spatial distribution and temporal trends.

In practice, these technologies are already being used:

In forests to monitor large mammals, forest birds and measure deforestation.

In oceans to survey coral reefs, cetaceans, ship noise and water quality.

In wetlands to track amphibians, fish, waterbirds and habitat dynamics.

In urban areas to map biodiversity in parks, green roofs and brownfields, or to monitor sensitive species.

However, major challenges remain:

Data quality: misidentifications, faulty sensors, bias due to the location of sampling points.

Data volume: millions of photos, hours of audio and long measurement series to store and analyse.

Interoperability: heterogeneous data formats and difficulty combining multiple data sources.

Capacity building: training local teams in installation, maintenance and data analysis.

Professional solutions, such as the platforms available in the Natural Solutions product range, help structure these data flows, automate parts of the analysis and make results directly usable for decision-making.

AI and machine learning for advanced biodiversity monitoring

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning play an increasingly central role in biodiversity technology. They automate tasks that previously required hundreds of hours of manual work, such as identifying species in photos or audio recordings.

Key applications of AI for biodiversity include:

Image-based species identification: computer vision models automatically recognise animals or plants in camera-trap or drone images.

Acoustic analysis: algorithms detect and classify bird songs, marine mammal calls or insect sounds in long-duration recordings.

Invasive species detection: rapid identification of new arrivals in an ecosystem, enabling early intervention.

Species distribution modelling: AI combines observation data, climate and land cover to predict where a species is present or likely to occur.

Extinction risk assessment: detection of worrying trends in populations and simulation of future scenarios.

Many open-source tools, collaborative platforms and professional solutions are used by researchers and NGOs. Providers such as Natural Solutions directly integrate AI capabilities into their platforms, making these technologies accessible to teams without in-house data science expertise.

However, the use of AI raises ethical and practical questions:

Dataset bias: if models are trained mainly on certain regions or species, their performance may drop in other contexts.

Algorithm transparency: understanding how models make decisions is essential for trust and scientific reproducibility.

Expert validation: AI should be seen as decision support, not a replacement for ecologists; human validation remains vital for sensitive decisions.

Data protection: locations of threatened species must sometimes be kept confidential to reduce poaching risks.

When used responsibly, AI allows a shift from occasional surveys based on a handful of samples to continuous, large-scale monitoring, paving the way for more reactive and predictive conservation.

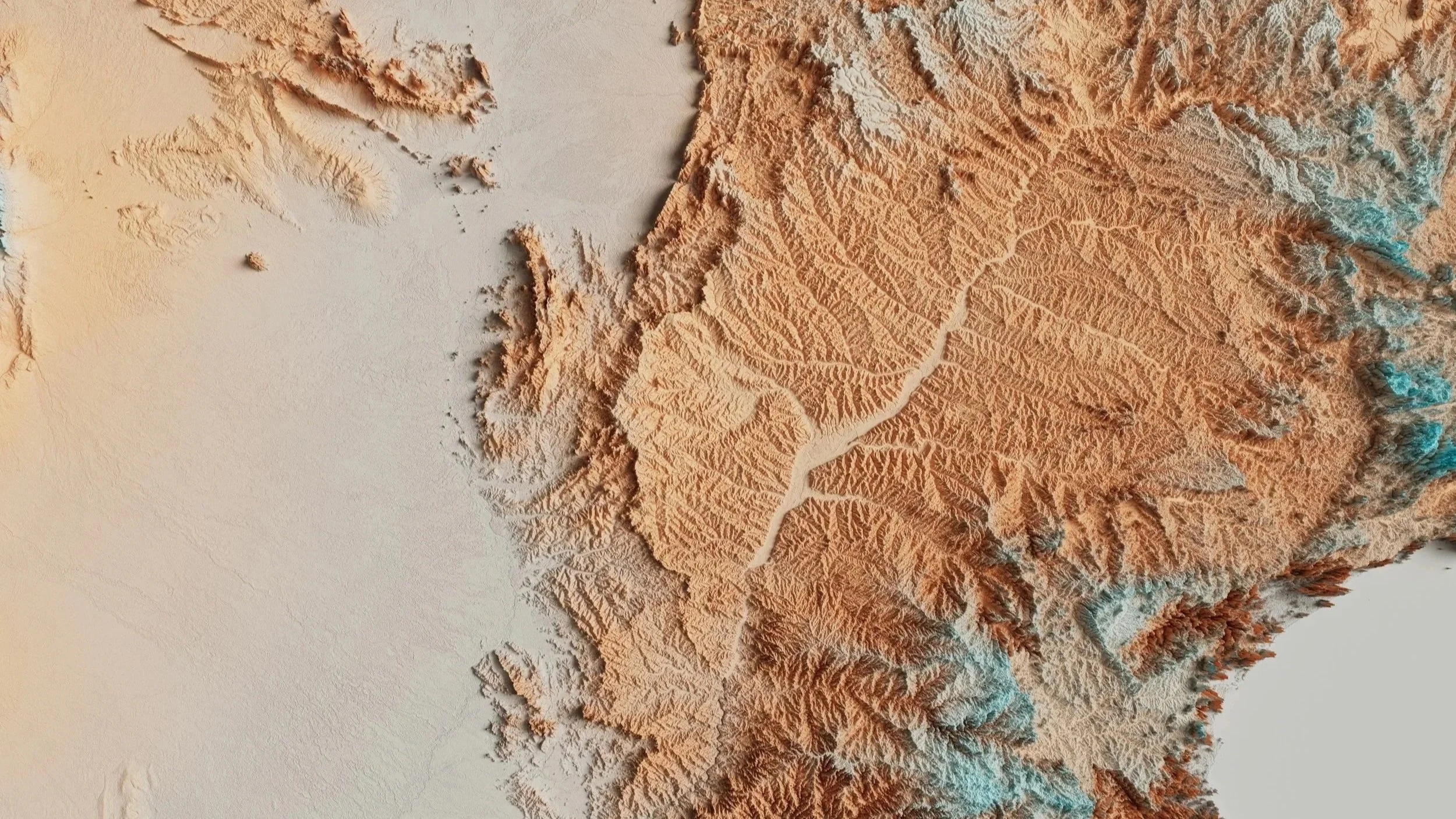

Remote sensing for landscape-scale biodiversity assessment

Remote sensing encompasses all techniques that collect information about ecosystems without direct contact, using sensors mounted on:

Satellites in orbit around the Earth.

Aircraft (planes, helicopters).

High-altitude platforms (balloons, pseudo-satellites).

For biodiversity, the most widely used remote sensing datasets are:

Multispectral satellite images, which measure vegetation (indices such as NDVI), land cover, moisture and land surface temperature.

LiDAR (laser-based remote sensing), which reconstructs in 3D the structure of forests, mangroves or emergent reefs (height, canopy density, vertical stratification).

These data enable:

Habitat mapping (primary forests, grasslands, wetlands, coral reefs, etc.);

Monitoring land-use and land-cover change (deforestation, urbanisation, habitat fragmentation);

Assessing ecosystem health (water stress, mass die-offs, coral bleaching);

identifying priority areas for conservation or restoration.

At global and regional scales, major programmes already rely on remote sensing for biodiversity: monitoring tropical forests, observing coastal zones, mapping habitats under environmental directives, and more. These programmes increasingly use online platforms and visualisation tools that are accessible to site managers and decision-makers.

Remote sensing, however, has limitations:

Spatial resolution: some satellites cannot detect fine features (hedgerows, small streams, ponds).

Cloud cover: in tropical regions, clouds can render some images unusable.

Cost and complexity of very high-resolution data or bespoke aerial campaigns.

The key is therefore to combine remote sensing data with field data. By integrating satellite imagery, sensor readings, naturalist observations and AI models, it is possible to produce more reliable maps and indicators, directly usable in software solutions such as those in the Natural Solutions product range, for example.

How to use drones in biodiversity conservation projects

Drones (remotely piloted aircraft) have become a powerful tool for conservation. They offer several advantages:

Very high-resolution data: detailed imagery that can reveal fine-scale structures, dominant plant species or animal tracks.

Access to difficult or dangerous areas: cliffs, marshes, dense forests, flooded zones.

Flexibility: the ability to schedule regular missions to monitor a site at relatively low cost compared with aircraft.

To use drones in a conservation project, several key steps should be followed:

Clarify objectives: animal counts, habitat mapping, restoration monitoring, anti-poaching surveillance, etc.

Choose the type of drone: multirotor (more manoeuvrable, for small areas) or fixed-wing (longer endurance, for large areas).

Select sensors:

RGB cameras for standard photo and video.

Multispectral sensors to analyse vegetation and plant health.

Thermal sensors to detect wildlife, especially at night or under partial canopy cover.

Plan missions: flight paths, altitude, image overlap, survey timing (for example, avoiding the breeding season).

Comply with regulations: drone registration, pilot training or certification, and any necessary permits.

Typical use cases include:

Wildlife surveys: counting seabird colonies, large mammals, nests or burrows.

Anti-poaching operations: discreet surveillance of protected areas, detection of suspicious activity.

Habitat mapping: monitoring vegetation, erosion, or the expansion of wetlands.

Restoration and reforestation monitoring: checking seedling survival, detecting mortality, measuring vegetation cover.

To maximise the impact of drone data, it is essential to:

set up data processing workflows (image stitching, orthomosaics, automated classification, integration into a geographic information system);

ensure operational safety (risk management, clear procedures);

involve local communities to share results, incorporate local knowledge and build support;

minimise disturbance to wildlife (appropriate altitude, limited flight time, avoiding sensitive periods).

Environmental data management platforms within the Natural Solutions product range can serve as a central hub to store, visualise and analyse drone data, and to combine them with other information sources.

Implementing biodiversity technology: strategy, partnerships and future trends

Integrating biodiversity technology into a project or conservation strategy requires a structured approach. It is not just about buying sensors or deploying an AI model, but about designing an end-to-end monitoring and decision-support system.

Key steps to define your strategy include:

Clarify conservation objectives: target species, priority habitats, indicators to track, regulatory obligations, funder requirements.

Map data needs: which variables must be measured? How often? At what scale (site, landscape, region)?

Select appropriate technologies: field sensors, AI, remote sensing, drones, citizen science apps, according to budget and internal capacity.

Plan data architecture: storage, formats, security, governance and user interfaces.

Plan capacity building: training, guides, documentation and expert support.

Success also depends on strong partnerships:

NGOs and associations for field expertise and community engagement.

Universities and research centres for methodological development, modelling and scientific analysis.

Technology companies such as Natural Solutions for software and hardware solutions, systems integration and technical support.

Public institutions for funding, regulatory frameworks and long-term programme support.

Emerging trends to watch include:

Embedded AI (edge AI) devices: sensors capable of processing data locally and transmitting only alerts or summaries.

Real-time biodiversity dashboards: instant visualisation of key indicators for site managers and decision-makers.

Citizen science applications: engaging the public to massively increase biodiversity observation datasets.

Digital twins of ecosystems: numerical models simulating ecosystem functioning to test management scenarios virtually.

To fund and sustain these systems, it is advisable to:

diversify funding sources (public grants, foundations, philanthropy, private-sector partnerships);

embed technology within multi-year programmes rather than one-off projects;

allocate budget for maintenance (sensors, servers, software updates);

invest in the continuous training of teams.

By partnering with experienced organisations such as Natural Solutions, it becomes easier to move from concept to implementation and to build a biodiversity monitoring system that is robust, scalable and genuinely useful for guiding decisions.

FAQ on biodiversity technology and conservation

What is biodiversity technology and how does it support conservation?

Biodiversity technology covers all technologies (sensors, software, AI, remote sensing, drones, citizen science apps) used to observe, measure and analyse biodiversity. It supports conservation by providing:

more accurate and frequent data on species and habitats;

advanced analytical tools to detect trends and threats;

reliable indicators to assess the impact of conservation actions and public policies.

How is technology used to monitor biodiversity in remote or sensitive areas?

In isolated, hazardous or ecologically sensitive areas, conservation teams mainly use:

Autonomous sensors (cameras, acoustic recorders, weather stations) powered by batteries or solar panels;

GPS tags to track animals without frequent human intervention;

Drones to map sites without physically entering fragile habitats;

Remote sensing (satellite imagery) to monitor vast territories without on-the-ground presence.

Data are then transmitted via cellular, radio or satellite networks to central platforms.

How are AI and machine learning used in biodiversity monitoring projects?

AI and machine learning are mainly used to:

automatically recognise species in images or audio recordings;

detect complex patterns in large datasets (population trends, responses to climate change);

predict species distributions or extinction risk based on multiple environmental variables;

generate alerts in abnormal situations (invasive species, poaching, rapid habitat degradation).

What is remote sensing for biodiversity assessment and who uses it?

Remote sensing involves collecting information about ecosystems using sensors mounted on satellites, aircraft or other aerial platforms. It enables practitioners to:

map habitats and track their evolution;

monitor deforestation, fragmentation and urbanisation;

assess the condition of vegetation and certain ecosystems.

Remote sensing is used by:

government agencies and local authorities;

research organisations and universities;

conservation NGOs;

companies committed to environmental responsibility.

How can I use drones safely and legally in biodiversity conservation projects?

To use drones in line with safety and legal requirements, it is important to:

understand the national regulations (drone registration, no-fly zones, maximum altitude, etc.);

complete appropriate training or obtain certification if required;

plan missions to avoid risks (people, infrastructure, sensitive airspace);

adapt flight plans to minimise disturbance to wildlife (timing, altitude, duration);

ensure traceability of collected data and respect confidentiality where necessary.

Ready to modernise your conservation work with cutting-edge biodiversity technology? Start by mapping your data needs, launching pilot projects that combine AI and drone-based monitoring, and building partnerships with trusted technology and conservation partners such as Natural Solutions to scale up your impact across your landscapes.